KILLING LINCOLN: Interviews, Historical Timeline & Behind the Scenes Look

Maj Canton - February 16, 2013

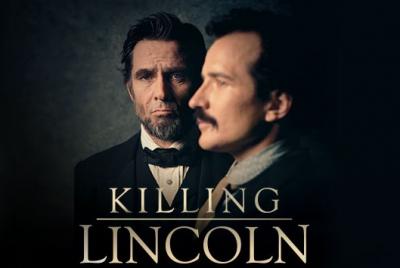

National Geographic Channel’s first original scripted drama, KILLING LINCOLN, presents one of the most significant events in our country’s history. With fresh historical insight, the film chronicles the final days of President Lincoln and the treasonous plot by one the most notorious, yet complex villains of all time. Based on the best selling book by Bill O’Reilly, the docudrama is narrated on screen by Tom Hanks and stars Billy Campbell as Lincoln and Jesse Johnson as John Wilkes Booth. KILLING LINCOLN dramatically counts down the President’s last days and actions leading up to the April 14 assassination at Ford’s Theatre: Lincoln has six weeks to live, days to survive, hours to breathe one last time ... and concludes with the aftermath of his murder. KILLING LINCOLN premieres Sunday February 17, 2013 at 8pm ET on the National Geographic Channel.

|

|

Interview with Billy Campbell who plays Abraham Lincoln

|

|

|

Question: Describe Lincoln in your own words. Billy Campbell: He was arguably our greatest president. He was self-taught, well-rounded, a complex and profound human being who did great things for our country. I can’t think of any American historical figure who is as justifiably revered, or who was as tragically fated.

Question: How did you prepare for or research the role? What were the challenges? |

|

Question: From THE KILLING to KILLING LINCOLN.... How was playing Lincoln similar to or different from other characters you have portrayed on TV and film? What was the draw? Billy Campbell: Well, Lincoln is an historical figure, obviously, someone who actually existed, so there’s an obligation to portray things as they were. I’ve never been part of a production with as strong a commitment to authenticity as this one. It was extraordinary, and highly comforting, and I was drawn to the part for all those very same reasons.

Question: How do you hope your portrayal of Lincoln is distinguished from other films out there? |

|

|

|

|

Question: You grew up in Virginia. Describe shooting in the Richmond area, where so much history occurred. Billy Campbell: It was thrilling. We filmed in buildings that Lincoln visited, on streets he walked. I stood, dressed as Lincoln, on some of the very same spots Lincoln stood! It was genuinely inspiring. And I got to visit with family and friends. The whole thing was magical.

Question: What do you make of the historical tie between Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth? Billy Campbell: There’s no way to separate them. They are forever entwined in a tragedy of Shakespearean proportion. You can’t talk about the latter part of Lincoln’s life without talking about Booth, or Booth’s life at all without Lincoln. Who knows what might have come to pass if one hadn’t been so obsessed with the other? How much either might have accomplished? How different our nation might be? But it’s as much Booth’s story as it is Lincoln’s, certainly.

Question: What’s next for you? Billy Campbell: I’m not sure. I have a few irons in the fire. I’ll take some time off though, after a busy year, go sailing. Do some writing, a lot of reading. I can say this, whatever comes after KILLING LINCOLN is liable to feel like a letdown, no matter how good it is. |

|

|

|

|

Interview with Jesse Johnson who plays John Wilkes Booth

|

|

|

Question: What was it about John Wilkes Booth that drew you to the role? Jesse Johnson: This character is its own history lesson. While I was in Europe working on another project, I picked up some books on John Wilkes Booth and started doing my research. I was immediately fascinated by the richness and complexity of the character as a man. The prevailing image that has been propagated about Booth is one of a demonic, mustache-twirling villain, and understandably so. But upon further investigation you find that he’s a rich and complex human being.

Question: Any hesitations on playing such a reviled, historic villain? |

|

Question: What did you learn about Booth’s craft as an actor? Jesse Johnson: Booth came from a family of actors. In 1800s theater, everything was huge and elevated. It was all about grand gestures, and his entire world is based around drama. His father was also an actor, and he brought his children up reciting Shakespeare.

Question: Describe what it was like to be an actor playing an actor. Did you feel any similarities? Most actors really thrive on recognition and notoriety, and Booth was so fixated on leaving his mark in this world (something far more achievable with film and television these days as opposed to the theater in those days) that once the curtain drops and the lights go out, all you are is a performer in the audience’s memory and maybe a visage in a newspaper article. I truly believe he wanted to do something that would ink him in the pages of history forever. And I certainly don’t mean to belittle his political cause, because I maintain that he TRULY BELIEVED in his actions and what he was doing, it just happened to coincide with this insatiable lust for fame. |

|

|

|

Interview with Erik Jendresen, Screenwriter & Executive Producer

|

|

|

Question: How does KILLING LINCOLN add to the story of Lincoln’s assassination? Erik Jendresen: It’s worth noting that not one of the cinematic portrayals of this event – from D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” (nearly 100 years ago) to Redford’s recent “The Conspirator” – has shown Booth entering the presidential box through the correct door! This project was created specifically to portray the assassination with historical accuracy – and by that I mean to dramatize everything that is known to be “fact-positive” about the event and also to embrace the way history “happens” – how the subjective experiences of the players were recorded and passed down through generations. The first step was to research everything that is known to be factual, including details that are rarely given attention in our medium (i.e., who were the specific soldiers who accompanied Lincoln to Richmond; what books were on Secretary of State William Seward’s nightstand; what specific weapons were used by the co- conspirators) and to make certain that these details are present within our camera’s frame without necessarily remarking upon them. One example of embracing how history “happens” is that we see the assassination of Lincoln from four different points of view: an “objective” one; two different versions based on the testimonies of theatergoers Lt. A.M.S. Crawford and William Ferguson; and a fourth based on the testimony of actor Harry Hawk. These testimonies were taken within hours of the assassination, yet the details fail to correspond. I feel quite confident that we have captured the “truth” about the events of April 14, 1865, in as precise a fashion as possible. |

|

Question: What are some of the historical discrepancies you found and how do you deal with it in the film? Erik Jendresen: One is whether or not Booth broke his leg when he jumped from Lincoln’s box onto the stage of Ford’s Theatre. None of the first-person eyewitness accounts describe Booth running off the stage in an awkward manner or hobbling; Booth did tell John Lloyd that he had broken it when his horse fell, and Booth’s journal entry can be interpreted in two ways. All of this is shown. Elsewhere, there are extraordinarily reliable witnesses and very respected historical figures who testify beyond a shadow of a doubt that during Booth’s autopsy, he did not have a mustache, and then there are witnesses at the time who state unequivocally that he did have his mustache. We show Booth considering shaving but deciding against it. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s precise words following Lincoln’s death are addressed in two different ways, and the reason why no one knows whether he uttered the words “Now he belongs to the ages” or “Now he belongs to the angels” is due to the fact that Cpl. James Tanner’s pencil broke.

Question: How does KILLING LINCOLN incorporate new research? |

|

|

|

|

Question: Does KILLING LINCOLN portray Booth differently than he is traditionally depicted? Erik Jendresen: For the first time, Booth is portrayed as the passionate and possibly brilliant man he was. He has been reduced by history to a two-dimensional, demonic, psychotic figure. The truth is quite the contrary. He was a highly respected actor doing things onstage that nobody had done before. He was pushing the edge of the envelope artistically and was on his way to becoming the greatest actor of his age. But then he became sidetracked by his misguided belief that everything that the Constitution stood for and everything that he believed in was being threatened by what he saw as an inferior president and a malevolent tyrant. He misread the situation extraordinarily but he believed in it fervently. The fact is that Lincoln stood almost alone in his own Republican Party in his determination to “let the South up easy” – to create a just and lasting and compassionate peace and to restore the Union by gentle means rather than by further punishing the South. Jefferson Davis himself would say the greatest tragedy to befall the South, next to the fall of the Confederacy, was the death of Abraham Lincoln. Booth, in seeking to avenge the South, actually killed the South’s best friend. It’s Shakespearean in its tragedy.

Question: How does Bill O’Reilly’s bestseller, KILLING LINCOLN, inform the film? |

|

Question: How does KILLING LINCOLN combine drama and documentary? Erik Jendresen: The assassination of Abraham Lincoln was part of a conspiracy to decapitate the government of the United States in one fell swoop – by killing the president, the vice president and the secretary of state. While the characters of Booth’s co-conspirators play a major role in our film, we don’t fully see their faces until the end – when Alexander Gardner takes their photographs. We see the real faces of these men, rather than those of the fine actors we cast to portray their emotions and physicality. And we have a storyteller, Tom Hanks, and his job is very specific to facts and figures and dates and times. He’s giving the viewer all the background information needed to appreciate and understand the context of the next moment of the story. And every time we drop into the action, we’re dropping into a feature film. In some ways it’s a hybrid of docudrama and feature film that hasn’t been done quite like this before. It’s absolutely a new style – a new way of approaching historical content – with 100 percent authenticity, full cinematic feature-film quality and a remarkable cast. |

|

|

|

Interview with Ridley Scott, Executive Producer

|

|

|

Question: What about this version (O’Reilly’s book) of the story made you think it would be a good fit for Scott Free? What attracted you to the project? Ridley Scott: What’s tremendously compelling about KILLING LINCOLN is that even though it is about a terrible tragedy in this country’s history—losing one of its greatest leaders—it is also a suspenseful thriller that takes audiences on a true ride. What people never knew, and what both the book and the film capture, is the great tale of action and conspiracy surrounding the manhunt for Booth. It is ultimately a fascinating story, and that’s what makes it the perfect fit for us at Scott Free.

Question: How does KILLING LINCOLN advance or expand the story we all think we know? Ridley Scott: KILLING LINCOLN is a true historical story that explores John Wilkes Booth’s actions before and after the assassination. We go into a life that has never been seen before from this perspective. And that life provides great insight into one of the biggest conspiracies in this country’s history. |

|

Question: From a producer’s standpoint, what was most fascinating about the assassination of Lincoln? What part of the tale were you eager to see adapted onscreen?

Question: Tell us about the actors. |

|

|

|

Timeline of Lincoln's Asssassination

|

|

|

|

||

| August 1864 (8 months left) |

While Lincoln is riding alone from the War Department to the Soldiers’ Home where his family stays during the hot summer months, a gunshot sends his horse galloping. Pvt. John W. Nichols helps to steady his horse and later makes a disturbing discovery: He finds Lincoln’s hat, lost during the horse’s gallop, with a bullet hole through the crown. Lincoln begs Nichols’ silence on the matter, assuring him it was an accident. |

|

|

|

||

| Feb. 5, 1865 (10 weeks left) |

Lincoln visits Alexander Gardner’s photographic studio with his son Tad. The photos are the last formal portraits ever taken of the president. |

|

|

|

||

| March 4, 1865 (6 weeks left) |

On the steps of the Capitol, Lincoln delivers his Second Inaugural Address. The speech is considered by many to be his second most influential address, after the Gettysburg Address., and adorns a wall at the Lincoln Memorial. John Wilkes Booth is in attendance. |

|

|

|

||

| April 2, 1865 (13 days left) |

Aboard the steamship River Queen en route to the warfront where General Ulysses S. Grant is poised to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Lincoln is said to dream of a president lying dead in the White House. |

|

|

|

||

| April 4, 1865 (11 days left) |

After walking the still-smoldering streets of Richmond, Lincoln makes his way to the surrendered home of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, who has fled his capital just 36 hours earlier. He sits at Davis’ chair and tells his son Tad, celebrating his 12th birthday, that it was from here that Davis conducted the war. |

|

|

|

||

| April 11, 1865 (4 days left) |

Following the surrender of General Robert E. Lee, Lincoln addresses a crowd from the North Portico of the White House, surprising many by outlining a generous and compassionate policy toward the South. Booth is there, along with several of his co-conspirators, and vows it is the last speech Lincoln will ever make. |

|

|

|

||

| April 13, 1865 (2 days left) |

Booth visits Grover’s Theatre and learns that Lincoln will attend a production of “Aladdin!” there the following evening. He informs his co-conspirators and sets their plan for April 14 in motion: Lewis Powell will kill Secretary of State Seward, and be led across the Navy Yard Bridge to Maryland by David Herold; George Azerodt will kill Vice President Johnson at his room at the Kirkwood House Hotel; and Booth will kill Lincoln at Grover’s. The following day Booth learns the president has changed his plans and will attend a performance of “My American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre instead. |

|

|

|

||

| April 14, 1865 |

|

|

| |

4:30pm (15 hours left) |

On the streets of Washington Booth encounters a fellow actor, John Matthews, to whom he gives a letter and asks that Matthews see that it is published in the next day’s National Intelligencer. Matthews was on the stage performing at Ford’s Theatre that evening, and the following day he burned the letter — Booth’s signed confession. |

|

|

||

| |

8:30pm (11 hours left) |

Lincoln and his wife Mary arrive at Ford’s Theatre. |

|

|

||

| |

9:40pm (10 hours left) |

Booth enters Peter Taltavul’s Star Saloon, next to Ford’s Theatre. When someone remarks to Booth that he’ll never be as good an actor as his father, witnesses report this alleged response: “When I leave the stage for good, I’ll be the most talked about man in America.” |

|

|

||

| |

10:15pm (9 hours left) |

Booth enters the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre and fires a single shot into the head of President Lincoln. After a brief struggle with Lincoln’s guest, Henry Rathbone, he then leaps from the box to the stage, where he shouts to the audience, “Sic semper tyrannis!” (“Thus always to tyrants!”). Simultaneously, Booth’s co-conspirator Lewis Powell forces his way into the home of Secretary of State William Seward, who is bedridden following a carriage accident, and stabs him. |

|

|

||

| |

10:35pm (20 minutes since Lincoln was shot) |

Booth arrives at the Navy Yard Bridge, his escape route into Maryland. Though no one is to pass over this bridge after 9 p.m., Sgt. Silas T. Cobb reluctantly allows him through. At Ford’s Theatre, Dr. Charles Leale and Dr. Charles Taft tend to the president’s wound. He is carried out of the theatre and across the street to a boarding house owned by William Petersen. Due to his height, they lay him diagonally on the bed. |

|

|

||

| |

11pm (45 minutes since Lincoln was shot) |

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sets up a headquarters in the back parlor of the house and issues emergency directives to police and military authorities to initiate a manhunt for the as-yet unknown assassin. Chief Justice David Kellogg Carter begins to hear eyewitness testimony of the crime. A boarder in the house next door, 21-year-old Cpl. James Tanner, a veteran and double amputee, offers his skills in shorthand to transcribe witnesses’ testimony. |

|

|

||

| April 15, 1865 |

|

|

| |

12:15am (2 hours since Lincoln was shot) |

Booth and David Herold arrive at Surratt Tavern, a safe house for Confederate spies owned by Mary Surratt, the mother of Confederate courier John Surratt. Herold’s job as part of the conspiracy was to lead Lewis Powell out of Washington after killing William Seward. But upon hearing cries of “Murder!” from the Seward house, he fled the scene, not waiting for Powell. At the Petersen house, Cpl. Tanner begins to take the eyewitness accounts of some of the nearly 1,500 people who witnessed the assassination. No two stories are alike. |

|

|

||

| |

4:30am (6 hours since Lincoln was shot) |

Booth and Herold arrive at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd in the hopes of tending to Booth’s broken leg. |

|

|

||

| |

7:22am (9 hours since Lincoln was shot) |

President Abraham Lincoln dies. Surgeon General Barnes says, simply, “He is gone.” |

|

|

||

| April 16, 1865 @ 1am (10 days until Booth is killed) |

Having left Dr. Mudd’s home with his leg splinted and with the aid of a crutch, Booth and Herold arrive at the home of Samuel Cox, a Maryland landowner active in the Confederate underground. Cox recognizes Booth and knows of his crime. With the largest manhunt in American history under way, Cox aids them in hiding in a pine thicket two miles from his home while they await assistance to cross the Potomac into Virginia. They will wait there for the next five days. |

|

|

|

||

| April 17, 1865 (9 days until Booth is killed) |

The head of the National Police Detective asks photographer Alexander Gardner to make copies of three pictures. It is the first time in U.S. history that photographs have been used on a wanted poster. Thanks in part to papers found in Booth’s room at the National Hotel, Lewis Powell and Mary Surratt are jailed in Washington, and George Atzerodt, who got drunk and wandered away from the Kirkwood Hotel rather than attempt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, is discovered hiding at his cousin’s home in Maryland. |

|

|

|

||

| April 23, 1865 (3 days until Booth is killed) |

Booth and Herald are finally able to cross the Potomac and land in Virginia. In the time they’ve been waiting, Booth has learned that despite the brutality of Powell’s attack, William Seward survived, and Andrew Johnson, who was to have been killed by George Atzerodt, is now president. |

|

|

|

||

| April 24, 1865 (2 days until Booth is killed) |

In the evening, Booth spends a night in the home of Richard Garrett. The next day Garrett’s suspicions are aroused, and Booth and Herold are sent to sleep in the barn. |

|

|

|

||

| April 26, 1865 (The day Booth is killed) |

In the early morning hours of April 26, the fugitives are surrounded by 26 members of the 16th New York Cavalry. Herold chooses to surrender, but Booth refuses, and Union soldiers set fire to the barn. Shortly after, Booth is shot through the neck by Sgt. Boston Corbett. After struggling for several hours, Booth draws his last breath shortly after dawn. |

|

|

|

||

| April 27, 1865 (One day since Booth was killed) |

Alexander Gardner is summoned to take a photograph at Booth’s autopsy. The glass plate is assumed to have been delivered to Secretary of War Stanton. The photograph has never been found. |

|

|

|

||

| July 7, 1865 (82 days since Lincoln was assassinated; 71 days since Booth was killed) |

Four of Booth’s convicted co-conspirators are executed. Lewis Powell, George Azerodt, David Herold and Mary Surratt are hung from a scaffold at the old Arsenal Penitentiary. Four others serve prison terms of various lengths. |

|

|

|

||

|

|

On the Set of KILLING LINCOLN

|

|

|

On a stifling July day, a boat pulls up to the shore of the Appomattox River and a familiar figure disembarks — tall, dressed in black, with a distinguishable stovepipe hat. As he makes his way up a rocky trail, followed by a group of men dressed as slaves and soldiers, he does so methodically, taking each step with great care. Finally emerging from tall grass into the sun, he enters full view and reveals himself: It is the nation’s 16th president, the iconic Abraham Lincoln, as portrayed by Billy Campbell. |

|

“All of these buildings are from before 1865. Lincoln himself was here at the fall of Petersburg,” says executive producer Mark Herzog. “While we’re using Petersburg for Richmond, the town was very important to the Civil War. We’re shooting among history here.” |

|

|

|